After days of wrestling through the complexity of place and people, we found ourselves in a Druze village with the best cup of tea I’d ever tasted in hand. As I sipped my heated, cinnamon flavored drink, shielded from the unrelenting sun in the coolness of a Druze home, I settled into my backless chair, not expecting to learn, for the first time, what hospitality really meant.

I was at a personal saturation point. I had learned and observed more than I had the capacity to contain. As I considered this, I heard our host say:

“Among our people, hospitality means that the guest becomes the resident and the resident becomes the guest.”

The conversation continued from there, but I heard nothing else.

“…the guest becomes the resident…the resident becomes the guest.”

In that statement, many things happened at once: I heard the voice of Jesus; I learned what courageous hospitality meant; I was confronted with my own feeble attempts at hospitality; and I discovered the way forward for Israelis, Palestinians, and all the rest of us.

If we could become people who embodied this philosophy of hospitality (which is nothing short of the Way of Jesus) then there would be no land grabbing or suicide bombing, no need for separation walls or barbed-wire, no more bullet-firing or rock-slinging. If we could become people who, in humility, offered residency to the guest, we would have peace.

Fixated on this new-found philosophy of hospitality, I began to wonder if it was simply theory or if it landed in reality. As the opposite of this philosophy informed the majority of our experience up to this point, I doubted very much that it was possible in practice…especially here.

I was wrong.

A Story of Courageous Hospitality: She Sang for Us a Song.

Fakhira was our Palestinian guide, but was far more than that: she was my friend. While she was still only our guide, she had told us that a day was coming when we all would be invited into her home. We were not few, so I was impressed by the level of hospitality that this would require. As the days went by, though, and as Fakhira became a friend, I began to discover just how significant hosting an American delegation would be to her and to her family.

Fakhira, you see, was one of four daughters, was single, and, much to her father’s chagrin, was involved in politics. He would have preferred that she stopped wasting her time, a risk to herself and her future, with political nonsense and that she would settle down, get married, and begin building a life.

“Are you excited?” she would repeatedly ask me.

“So excited!” I would respond. And I was excited. In the days leading up to our visit, I saw in Fakhira how meaningful this moment was going to be for her.

When we arrived, her entire family had gathered. Mother, Father, Sisters, Nieces, Nephews. Everyone was there to welcome Fakhira’s American friends into their home. They invited us in to the re-arranged living room and, plate after plate, began serving homemade delicacies that, no doubt, had been days in preparation. Dishes of sliced watermelon and plastic bottles of water and soda made round after round until none of us could eat another bite or drink another sip.

Fakhira’s father stood to his feet and cleared his throat.

Silence settled in the room.

“You are home with us…this is your home…we are the guests.”

It was the same quote from earlier that day. And it was true, I felt like I was home.

As his introduction and welcome concluded, the primary facilitator of our learning delegation, sensing the importance of this moment, rose to thank Fakhira’s family but did not stop there. He went on to speak words of significance and virtue over Fakhira, to affirm the work that she was doing, and to give his support to her ongoing work and study in conflict resolution.

Both Fakhira and her father were in tears. With a group of Americans in a Palestinian home, a Palestinian father embraced the treasure that was his Palestinian daughter. In that moment, he recognized that she was, in fact, building a life: it was a different, meaningful kind of life that will matter for years to come.

The sound of Fakhira’s niece singing to Jesus in Arabic set the soundtrack for the transformation that I saw occurring between father and daughter. It was good…very good.

When the song ended, I asked Fakhira to take the microphone and to sing. Sheepishly, she turned down the invitation, but I would not be swayed. I don’t know why, but I wanted Fakhira to sing.

“Fakhira!” I began to chant. “Fakhira! Fakhira! Fakhira!” My friends joined in; so did her sisters, and mother, and father. Before the long, the entire room shouted “Fakhira! Fakhira! Fakhira!”

She looked at me with eyes that said: “You started this! You’re in big trouble with me!”

I winked back and smiled, standing and chanting all the louder: “Fakhira! Fakhira! Fakhira!”

She took a step toward the microphone and the room went berserk!

“I don’t sing.” were her first amplified words, “but I’ll sing. I’ll sing a song that has much meaning to me.”

She sang for us in her own home and in her own language a song about a Jesus who knows her name.

It was an inspired moment. All of us were spellbound.

Three days later, as Fakhira spoke to us about the most significant moments of our time together, she looked directly at me and said: “I want to thank you for strengthening me to sing. I had been disconnected from my identity as a Jesus Follower.”

Another Story of Courageous Hospitality: Bread and Eggs @ 3:00am.

The learning delegation had come to a close. My American friends were getting on airplanes while my Palestinian friends awaited my arrival in the West Bank.

From behind, I heard a metallic click and a voice yell, “Stop!”

I stopped and slowly turned my head. My heart was pounding. The sound of blood pumping through my ears was deafening. The defender began walking toward me, machine gun in hands.

“Passport!”

I dug in my shirt pocket for the little blue booklet that gives me permission to go virtually anywhere on the globe. Finding it, I opened it to my picture and handed it to him.

Seeing that I was American, he softened a bit: “Where are you going?”

“To the West Bank.” I said. Wasn’t this obvious?

“Why?” he asked as he paged through my passport.

“Glad I just got my passport renewed!” I thought to myself as I could only imagine what he would have done had he seen where else in the world I’d been.

“To see some friends.” I responded, trying to shield the anxiety in my voice.

He looked at me quizzically.

“Friends?” he asked. “How do you have friends in the West Bank?”

Not waiting for me to answer, he handed my passport back: “This is a military only entrance. Entrance for civilians is there.” He pointed over my left shoulder and walked away.

“Thank you.” I said.

No response.

I returned my passport to my shirt pocket, tightened my straps (again) and began to pull my suitcase toward the civilian entrance.

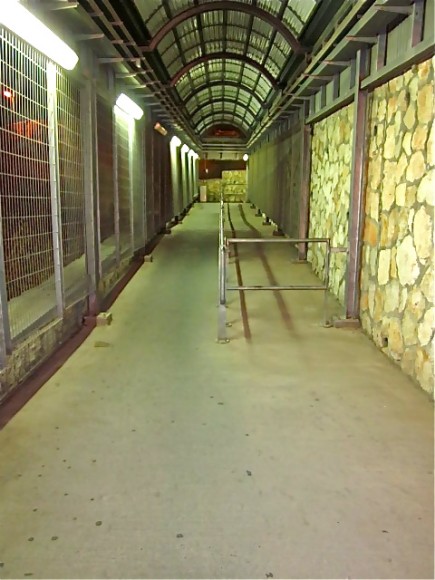

The Checkpoint is a fascinating experience. Composed of a maze of metal detectors, manned & armed security booths, and cages that route human beings like cattle back and forth before spitting them out on the Palestinian side. the Checkpoints are intentionally designed to dehumanize, humiliate, and irritate. They seem to be efficient at doing all three. No cameras are allowed, but (somehow) I found this picture on my camera by the time I got through.

Now, it was nearly 1:00am. I was approximately four hours late, yet, parked in the darkened streets of the West Bank was my friend Mahmut, the orange glow of a newly lit cigarette illuminating his silhouette.

“I’ve been waiting for your arrival, my friend.” he began without a hint of frustration. It seemed as though my arrival was worth his wait. We sped through the streets of Bethlehem to the home of his uncle, Nabeel.

“You are welcome!” was Nabeel’s greeting to me accompanied by a warm smile, a firm hand-shake, and, quickly thereafter, a cup of Arabic coffee. It was nearly 2:00am as we sipped our coffee together under the same stars that had, 2000 years prior, announced the arrival of One far more significant than I to this very place.

“Are you hungry?” Nabeel asked.

I was, but it was 2:00am. “I’m fine, thank you.” I lied.

With the taste of coffee in my mouth, Nabeel showed me his home and to my room. I quickly understood that I was being given Nabeel’s own room.

“Nabeel, where will you sleep?” I wondered aloud.

“The couch.” he said.

“Thank you, Nabeel.”

“You are welcome.”

Having cleaned up for bed, I entered into the room where Nabeel would sleep for the next three nights. “Good night, my new friend.” I said, hand over my heart in a sign of deep gratitude.

“Not quite yet.” was his riddled response. “Mahmut has gone to get you food.”

It dawned on me then that Mahmut had left the moment I had lied. I hadn’t seen him since.

Thirty minutes later, at 3:00am, he returned with homemade bread still warm from the oven and six hard-boiled eggs.

Met by my bewildered look, he shrugged his shoulders and said “You looked hungry…lucky for you, I know when and where they make the bread.”

Later, with a full stomach and with hand over heart for the second time in an hour, I managed: “Thank you!”

“You are welcome. When you are in my home, I am the guest.”